Bringing senses to the BFI National Archive

In January to March this year the BFI’s Collections Systems team were involved in a pilot project with The Sensational Museum, an interdisciplinary research project rethinking the role of senses in museums. The project’s aim is to explore how to make the museum experience less sight-centric, and our part in the project was around reimagining how Collections Management Systems, like the BFI’s Collections Information Database (CID), could capture and utilise multi-sensory data to make collection records more inclusive and accessible.

The BFI isn’t a museum with a traditional object exhibition space for the public; rather the BFI National Archive is a huge collection of moving image data with its own paper-based archive and a library collection, so we were able to bring a unique perspective to the project. Exploring the senses you experience whilst watching a film or TV episode on a screen can be quite different to the senses experienced seeing a physical object in a museum!

During the project we delved into understanding ten prominent sensory systems, tested a prototype system, and documented our sensory interactions with items in the BFI collection. It was fascinating and enjoyable digging into the collection, taking the time to focus on describing our personal sensory interactions with items. For example, the evocation of proprioception (spatial awareness) in scenes of vast countryside and enclosed spaces of buses and caravans in an episode of Johnny Vegas: Carry on Glamping; or the imagined sensation of touching silk and velvet from a Dracula costume design, conjuring a fond emotional response for the iconic character and costume. But we also considered how we could record sensory data about our collection spaces, for example lighting, temperature, heights and sounds in the archive stores, and how displaying this data could make our spaces more accessible.

We have also enjoyed sharing our findings with colleagues in the BFI through internal blog posts and ‘Show and Tells’, featuring a chilled-out narrowboat journey! Being part of this pilot project has been an interesting and rewarding insight into sensory thinking with our collection and has sparked many ideas on how we can make the BFI’s collections more accessible, both to the public and to BFI staff, through enhancements in our CID systems.

– Nicola Regan, Systems Support Specialist

Sandy Coloured Lobsters? Searching for an Ealing legend in a 1940s cinema commercial

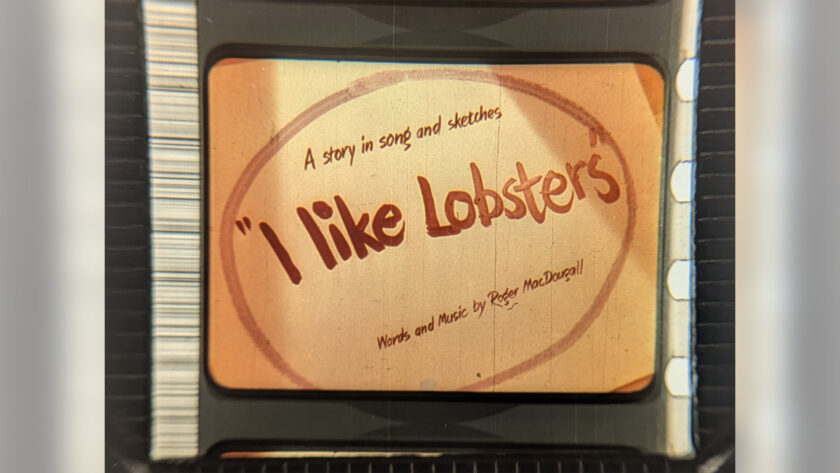

An email from diligent animation researcher Peter Hale recently prompted me to look at a nitrate print in the collection with the intriguing title “I Like Lobsters (Geraldo’s Orchestra)” from 1943.

The existing catalogue description described it as a musical, with the vague synopsis “A story in song and drawn sketches”. George Evans was credited as the singer, and Roger MacDougall as the man behind the words and music. The technical data recorded that the 35mm reel was around 300 feet long, had sound and was in colour, but also incomplete.

The film was safely retrieved from the BFI National Archive’s Master Film Store in Gaydon and acclimatised so that I could take a closer look on a winding bench. Peter had speculated that the film might be a cinema commercial, and that was confirmed by the opening credit for “JWT” – the adverting agency J Walter Thompson which had invested heavily in film from the late 1930s onwards. Roger MacDougall worked at JWT along with his cousin Alexander Mackendrick, who would go on to greater fame as a director, particularly of Ealing comedies such as The Man In The White Suit (1951) co-scripted by MacDougall.

In later life Mackendrick was rather dismissive of his origins in advertising, but it was in many ways the perfect unofficial film school. He was particularly involved in the scripting, storyboards and character designs for cartoon commercials made by George Pal, Anson Dyer and Halas & Batchelor, and remembered fondly by those who worked with him.

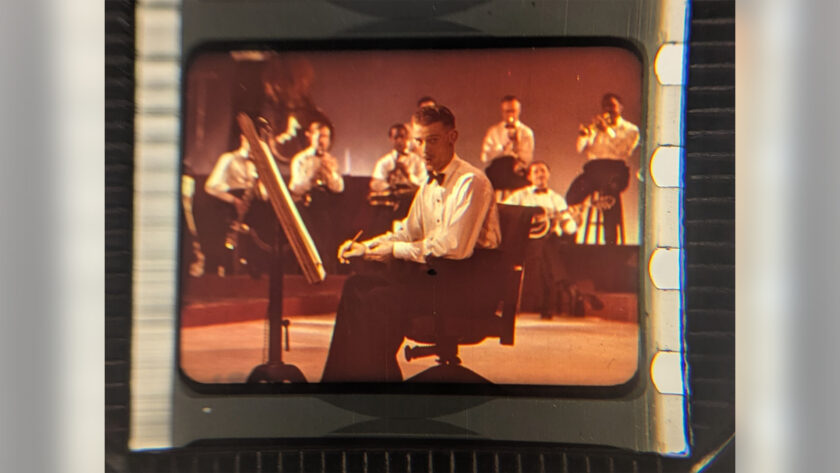

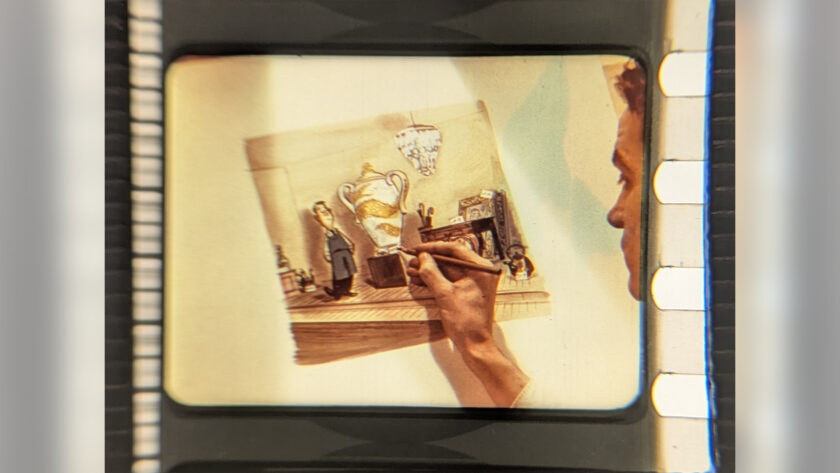

“I Like Lobsters” is not animated but makes use of a series of still cartoon drawings to illustrate a comic song. Were they Mackendrick’s? He is not credited at the start of the film – not uncommon in advertising – and the end of the reel is missing so no help there. Onscreen it is the singer George Evans who poses at a drawing board in front of Geraldo’s orchestra… except for one close-up shot of the hand of the artist. Surely that is Mackendrick’s distinctive profile at the edge of the frame? It was enough proof for me to update our catalogue record with a provisional credit, along with a general spring clean of the record.

Part of that clean-up involved a correction to the film’s technical description, in particular the reference to it being “2 strip Technicolor”, a two-colour process that had long been superseded by 1943. The opening of the film clearly states that it was made in Technicolor, but the dull, unusual palette of the films’ images does seem a long way from the three-strip “Glorious Technicolor” look that had become almost synonymous with the process but was actually the fourth version of the company’s colour system. Examination on the bench revealed remnants of three dyes dotted around the film strip, so it is three-colour. Intermittent blotches of blue in random frames suggest that the unusual tones and subsequent misidentification were possibly just a result of faults in printing. Colour was rare in cinema commercials throughout the Second World War as it was held in reserve for training films and prestige productions. It’s likely that the straightened times lead to further compromises in the handling of colour in both production and its distribution.

So, with some increased clarity but further tantalising questions dangling another intriguing footnote in British cinema history returns to the vault to await its next outing – with the additional information ascribed to it hopefully making that happen all the sooner.

– Jez Stewart, Curator (Animation)

The Inside the Archive blog is supported by the BFI Screen Heritage Fund, awarding National Lottery funding.