Script supervisors’ archives: a Special Collections show-and-tell

On Saturday 18 January, Wendy Russell, Helen Hanson, Lily Cheng and I had the pleasure of representing Special Collections at the Woman With a Movie Camera Summit. In our event, ‘Show and Tell – What Archives teach us about Continuity Work’, we presented items from our collection that highlight the often-overlooked contributions of script supervisors to film history.

Our show-and-tell followed on from ‘The All-Seeing Eyes: Script Supervisors and their Archives’, a panel discussion featuring Melanie Williams, Wendy Russell and Helen Hanson. Melanie gave an overview of the formidable responsibilities required of a script supervisor and how their work has been historically sidelined and diminished. Wendy illustrated how archival description, deaccessioning and repatriation can re-centre the script supervisor in film history. Helen spoke about Penny Eyles as script supervisor on Gosford Park and how Eyles’ script documents the work of other women onset. The panel did an excellent job of illuminating the demanding, essential role of the script supervisor, and how archives can foreground their work.

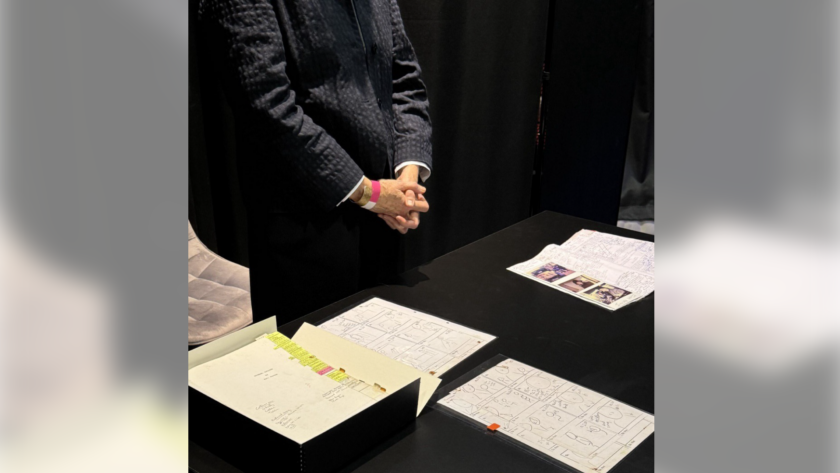

So, it followed on wonderfully that we were able to exhibit several continuity scripts from our collections. For grasping the depth of skill, attention and dexterity required of a script supervisor, there is nothing better than a material continuity script. The weight of a folder balanced on one arm, with a Polaroid camera, note-taking equipment, a typewriter, staplers, tape and other supplies – all of this is a lot easier to imagine while looking at the actual material.

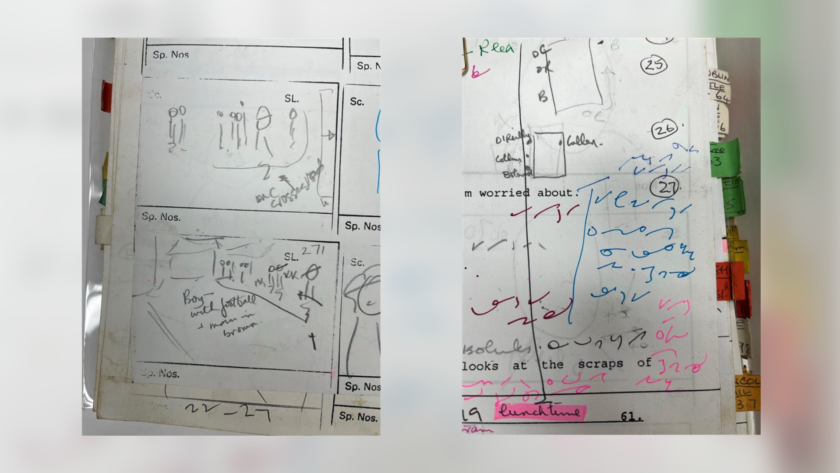

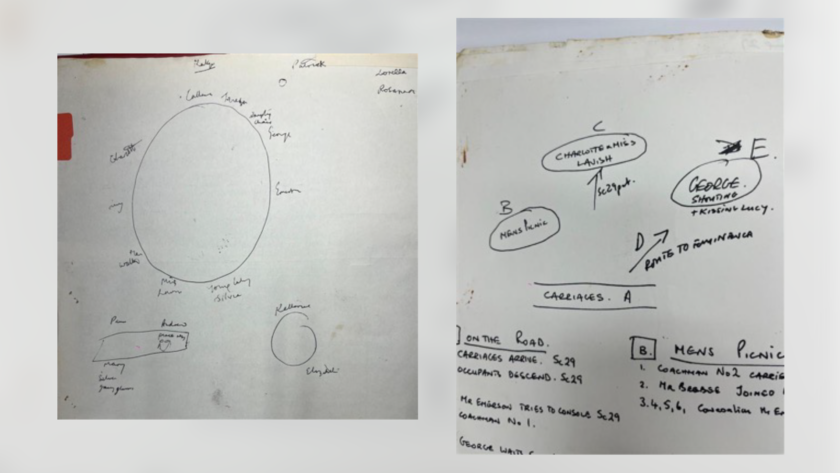

Helen showed part of Penny Eyles’ continuity script for Gosford Park, alongside Pat Rambaut’s script for Michael Collins. Rambaut drew quick sketches of each set-up (see below). These sketches detail the direction actors are looking in each scene, allowing her to preserve ‘the line’, or the onscreen connection between one actor and the next. Script supervisors would have had to record and access overwhelming amounts of information, and Rambaut’s colourful tabs and notes are a distinctive, intricate system of organisation. She learned this method of using tabs to easily access different shooting locations from Renée Glynne (a prolific script supervisor – keep her name in mind!), showing just how important support and communication was for transmitting the craft.

Eyles worked with both Polaroids and small sketches for Gosford Park, and primarily in pencil. It was a wonderful comparison between the unique methods of different script supervisors.

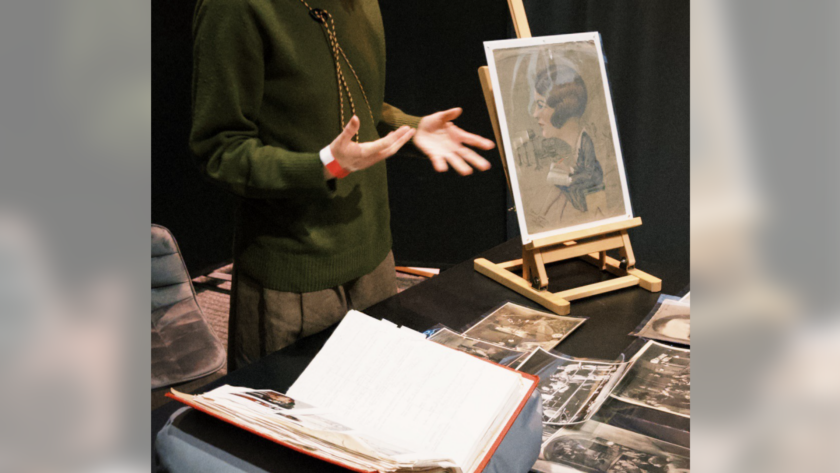

Wendy, meanwhile, displayed Penny Eyles’ continuity script for My Beautiful Laundrette, as well as photographs from the Helène (‘Nellie’) Peacock collection. Peacock was a script supervisor on numerous films, and the photographs demonstrate her vital role in early film history. However, she remains unmentioned in many film credits. During the panel, Wendy described how, through clues from the photographs, we can begin to identify the films that Peacock worked on. At the show-and-tell, several attendees got involved with this engaging detective work, examining the photographs to see if they recognised any films.

However, messages to Peacock on several of the photographs from male cast and crew members show their, at times, patronising attitude to her work. These photographs are a clear insight into the importance of her role, but also the frustrating ubiquity of its dismissal. By bringing out these photos, Helène Peacock can regain her place in film history.

I showed Renée Glynne’s continuity script for A Room With a View, in its original (and full to bursting) red folder. I love her unique method for capturing the totality of a scene – she’d cut out Polaroids and stick or staple them together to create panoramas. It’s an inventive workaround and shows how she was adapting the supplies to hand.

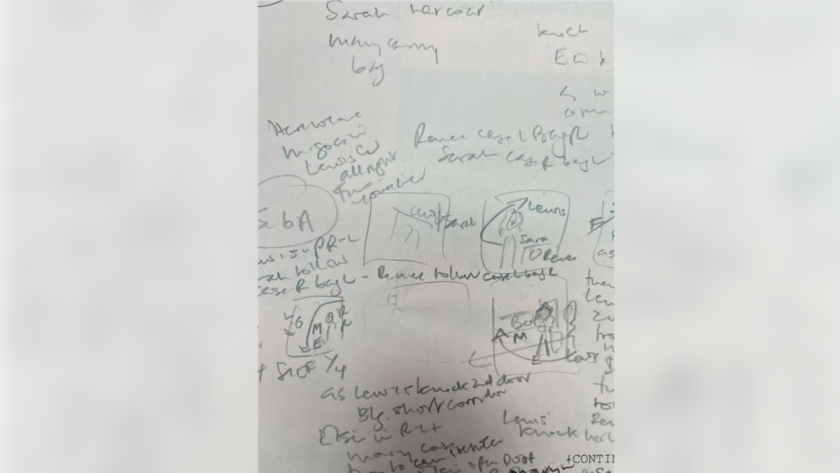

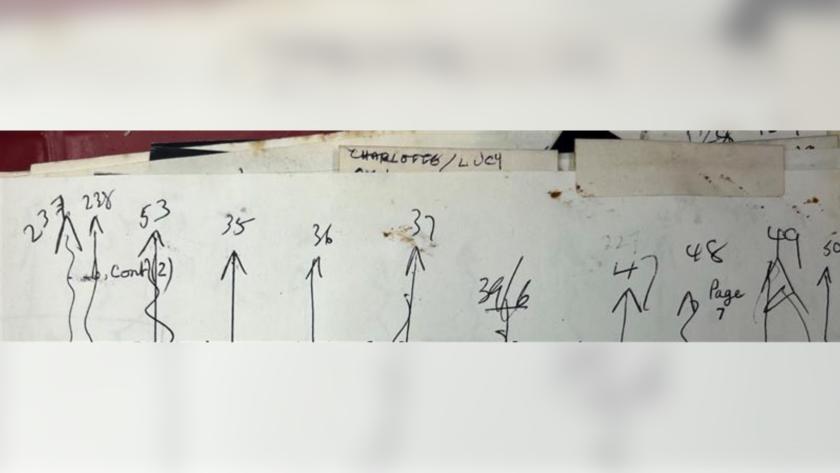

Her notes are extensive, detailing when maids enter and leave, when actors sit and eat, all the camera set ups and the positions of actors at the table. Below, you can see the top of a page from her script. Each number denotes a different set up that she would have been tracking through the scene – 11 in total! It’s a gorgeous, detailed script, and it was amazing to show it off to such an enthusiastic audience.

One of the highlights was talking to current script supervisors who attended the event, and the scripts sparked conversations about how the role has changed. A back-and-forth between two script supervisors about different apps for tracking continuity was delightful – the work remains so personalised and individual in the digital age. However, several also mentioned how undervalued script supervisors still are, especially on larger productions. Exhibiting their work in our collections is a way we can begin to redress this dismissal.

Overall, it was a fantastic event, and a great outing for Special Collections. It was so valuable to share the work of script supervisors in our collection, especially with such an enthusiastic crowd. We’re looking forward to holding similar events in the future!

– Eva Norton, Archives Assistant

Special thanks to Helen Hanson for being an honorary member of Special Collections for the day. Thanks also to Lily Cheng, who designed our wonderful poster, stewarded and photographed; to Tabitha Austin, who condition-checked all our items for display; and to Wendy Russell for organising the event.

AI altered vocals in Emilia Pérez

You may be aware of the recent controversy surrounding the use of AI technology to alter vocal performances in Oscar nominees The Brutalist and Emilia Pérez (see The Guardian article The Brutalist and Emilia Pérez’s Voice-Cloning Controversies).

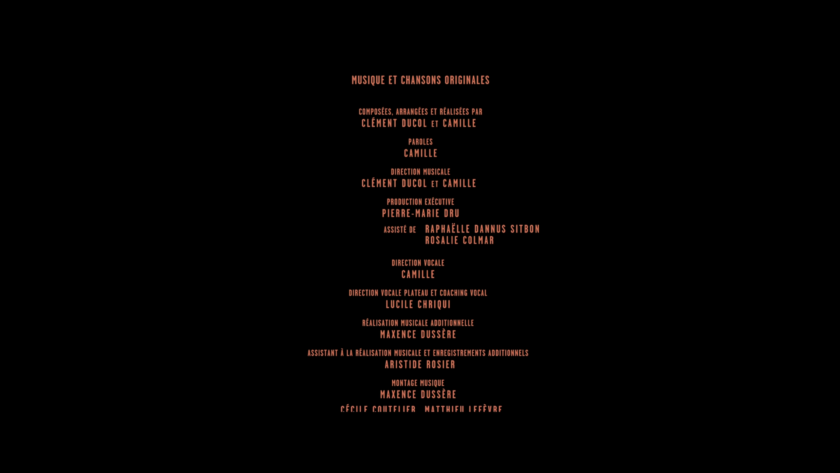

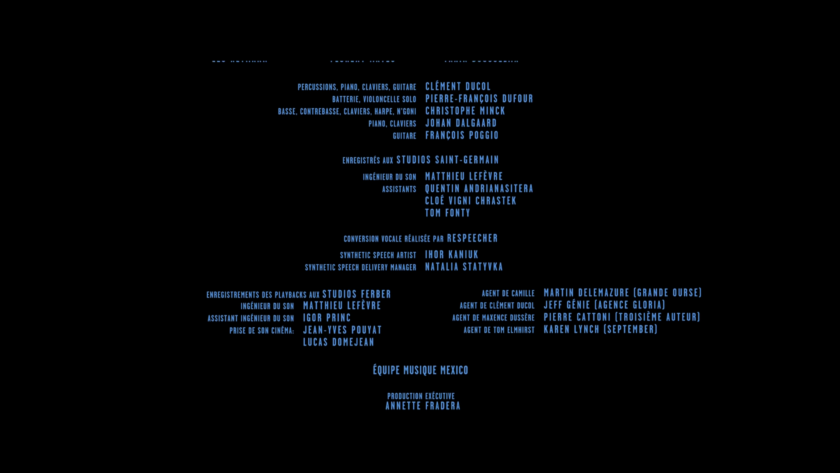

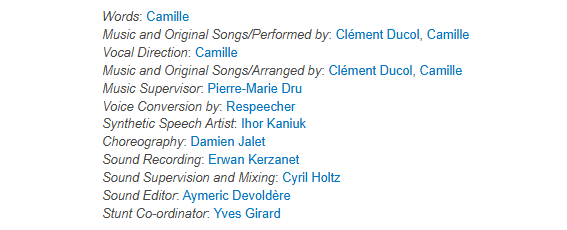

In an interview at last year’s Cannes Film Festival (conducted in French), the film’s re-recording mixer Cyril Holtz (credited onscreen for ‘Supervision Sonore et Mixage’) discussed how the voices of singer-songwriter Camille Dalmais (credited under her mononym Camille) were blended with those of lead actor Karla Sofia Gascón to create what he described as “la voix chimérique.” This was achieved using “la clonage de voix” of Camille through Respeecher, a Ukrainian software company specializing in speech synthesis that enables one person to speak in the voice of another via AI. Holtz also elaborated on how modifying the timbre of Gascón’s voice across different scenes served both a diegetic function and reflected post-transition changes in her vocal tone.

Thanks to the BFI documentation team’s access to Netflix, we’ve confirmed credits directly from the streaming release of Emilia Pérez. As a musical, it naturally includes an extensive list of music-related credits spanning composition, song lyrics, arrangements, performances, music direction, and voice coaching. The recent media attention surrounding the film’s innovative sound mixing has also highlighted some unique aspects of its production, shedding light on credits that might otherwise have been overlooked.

While non-UK films are typically catalogued with a focus on key production roles, we have the discretion to include additional credits when they provide notable context or value. In this instance, both Respeecher and Ihor Kaniuk have been added to our Collections Information Database record as a result.

This marks a pivotal moment before such technologies and workflows—like AI-driven voice cloning—are likely integrated into mainstream post-production sound processes, much like the adoption of image-based large language models into VFX workflows. Capturing this information now ensures we document these groundbreaking practices while they remain distinct and novel.

Similar controversy plagued Rami Malek’s Oscar winning performance in Bohemian Rhapsody. The film’s producers claimed that the songs in the film merged Malek’s vocals with that of Freddie Mercury sound-alike Marc Martel and “vocal stems” (isolated vocal tracks) from the Queen archive. In Contrast to Emilia Pérez that was the result of conventional mixing rather than AI, and the film’s re-recording mixer/music mixer Paul Massey has stated that “99.9%” of the singing in the film is Mercury”.

– James Taylor, Documentation Editor

The Inside the Archive blog is supported by the BFI Screen Heritage Fund, awarding National Lottery funding.